- Home

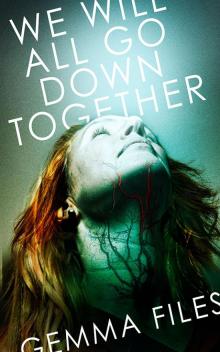

- We Will All Go Down Together (v5. 0) (epub)

We Will All Go Down Together Page 4

We Will All Go Down Together Read online

Page 4

Last week, the Ontario Provincial Police called to tell me they’d finally found my car. It was sitting by the side of a dirt road with no real name, a rural route half-on and half-off the Sidderstane family’s property outside of Overdeere. I asked them if it was near something called the Lake of the North, and they said yes. They told me it was within walking distance.

The OPP offered to take me up, and I agreed. The car was covered in dust and dirt, like someone had buried it. I asked them if I could get them to wait while I went over to the lake, just to check for any signs that Galit had been there, and I think the officers maybe felt sorry for me, and that’s why they said yes. One of them stayed with the car, while the other came with me.

It’s a weird area. The Ontario Field Naturalists guide says it’s all limestone and karst topography, full of hell-holes where the upper layer’s dissolved in water. There are barrens for miles on either side: dank marshes, scrubgrass, oak shrubs in shallow soil. Makes me wish I’d paid more attention in geography, so I could figure out if any of that’s even supposed to happen in Northern Ontario or not.

I asked the officer—his name was Nicholls—if this was Dourvale. He said Dourvale was kind of a local joke, like when tourists say they’re looking for Overdeere and you say “over where?” Except that the point is there just is no place called Dourvale, and neither of us could really explain why that’s supposed to be funny.

The Lake of the North comes up fast, out of nowhere. Galit would probably say it’s the colour of pain, because she’s always been good at stuff like that. That’s one reason why we worked so well together.

Nicholls and I walked most of the way around it, which took a while, but there was nothing there, aside from the lake itself. So I went back to my car. I found her laptop in the back seat.

I filed a missing-persons report, went home, and noodled around on her computer, but it was like it’d been corrupted—every file I opened up was just wild text and Wingdings. Then, eventually, it froze and shorted out. It’s still fried.

Yesterday, my server told me I’d been bouncing emails, so I did the dance, and I found something from her lurking in my backlog. The date said she sent it on September 10, one day shy of 9/11. It had attachments: an .mpg and three photos, all sent from her phone, but I’m not going to post a link to any of them. I wish I’d never seen them, or heard it.

Fuck.

Never mind what I wish.

I listened to the song three times, and it’s definitely Galit singing from someplace outside, all this ambient noise in the background: wind, leaves, something that almost sounds like breath, or whispering. The lyrics go like this—

At the Lake of the North my darling fell

And pulled me with him into Hell.

By waters cold and deep and black

He took my blood, I took it back.

He cut my throat from ear to ear,

He killed my babe, my own, my dear—

Made us a song sung up, sung down,

A song sung deep from underground.

I owe him naught. He owes me all.

And those who hear this hear my call.

Like I said, I’m not posting the photos, but I’ll describe them. They all look like they were taken on the shore of the lake, looking over towards where Dourvale should be, and when you see them at first, they don’t seem to be of anything except trees and scrub and swamp on a low, grey day, the sky full of clouds. But then, in the third one, if you stare at it long enough, you can see Galit standing in the shadow of one of the nearer rocks, surprisingly close by—I think the reason that she doesn’t show up the first few times is that her hoodie is practically the same colour as the shadow itself, and it’s pulled down over her hair. What I still can’t understand, however, is how she’s taking the photo, let alone sending it, since she must be eight feet away at the very least.

Look close enough, at any rate, and you see Galit. Look even closer, and you may (like me) think you see another woman with red hair standing right behind her—face indistinguishable, just that blazing, blowing hair, and Galit looking away from her, as though she doesn’t even realize she’s there.

So there’s Galit looking straight into the phone while the woman reaches out to touch her, so soft she wouldn’t have any warning, and the woman’s fingers are so much longer than they have any right to be: long, and thin, and slick, and boneless. Like eels from deep underwater shining with their own sick light, a light never meant to meet the surface air. Like long, white worms.

That’s what Galit would probably say they were like, anyway.

October 8, 2004

I erased the photos and trashed the .mpg this morning, after I met Galit’s boyfriend, Sidderstane, on the street outside my condo building. It’s icy out there, so I was watching my feet, not where I was going, and he was right in front of me before I knew it.

He said he wished he’d never met her. I said me too. He said I could look for her, I could maybe get her back, if I did it the right way. I said I wasn’t looking to go back up to Overdeere anytime soon. He said that was probably good, because they’d probably like for me to try.

It was all I could do not to take a swing at him, the smug son of a bitch, but I have to admit he did look pretty rough. His eyes were all slick and shiny and his lids looked really raw, too—like he’d been up all night crying, or at least rubbing at the sockets.

He said he should have stayed away from her, should have known that whatever he took a liking to, they’d know. He said: “But we do love to be sung of, always. It reminds us what we are.”

He said a bunch of stuff, and I was on the verge of asking him what the hell he meant by any of it when he just suddenly turned and walked away, instead. So I ran after him, but he was gone by the time I came around the corner, and I mean gone. The whole street was empty.

All right, well. I suppose that’s it for me, until I get some sort of word about what happened to Galit, or about anything. In the meantime, a big thank you to everyone who reads this blog. Thank you for caring about her. I know she’d say the same, if she was here.

I’ll keep in touch.

On February 17, 2005—after three months of non-payment—Galit Michaels’ blog was finally deleted from Folksinger.net. Her missing-persons file remains open with the Metro Toronto Police Department as well as the Ontario Provincial Police.

Investigation and interviews in the Overdeere area—primarily with hikers and transients rather than citizens—have produced unreliable witness reports of music heard “seeping up” through the loose rim of rocks and earth near the Lake of the North’s “Dourvale shore.” The most frequent description is that of a girl singing from too far off for her words to be easily understood.

As yet, none of these reports have been successfully substantiated or disproven.

BLACK BOX (2012)

The Clarke Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s attendants had Carraclough Devize dolled up and waiting for him when Sylvester Horse-Kicker arrived, very slightly late, due to a winning combination of parking, streetcar maintenance on Spadina—Toronto’s only got two seasons, boy, winter and construction, so watch out, his Mum had said, when he’d told her getting into the Freihoeven Institute’s Placement Program meant he’d be moving to the City—and a plague of migrating aphids filling the downtown core with the disgusting equivalent of green hail that squirmed when you wiped it away. She stood in the corner of the room like some reversed still from a lost Kurosawa film (Kiyoshi, not Akira), both taller than you’d think yet thinner, with her colourless mass of hair hanging down and her glasses angled so the light erased her eyes.

On closer inspection, he saw that those white things poking from her sleeves weren’t cuffs, but bandages.

“Miss Devize? I’m—”

Impossible to tell if she looked up or not, her voice all-but-affectless, as ever. “We met last year. The Eden Marozzi inquiry—those diora

ma photos. Abbott asked me to consult.”

“Yes, absolutely, sorry. It’s just . . . we didn’t talk much. I didn’t think you’d remember me.”

A shrug, one no-brow slightly canted, as though to project: Well, there you go. And—ugh, could he actually hear the echo of those same words trace his inner ear with sticky film, like walking through a spiderweb and only noticing it later?

I’m in the wrong damn job, if psychics creep me out this much.

Devize smiled, as though he’d made the remark out loud. As though he’d meant it as a joke.

“Abbott’s note mentioned storage,” she said. “So that means an item assessment.” He nodded. “Then I’ll need to drop by my office, get my camera. It’s in—”

He held it up: a vintage Polaroid One-Step, rainbow swoosh and all. Christ knew where she got the film. “Abbott told me,” he explained, unnecessarily.

“Of course.”

In the seven years he’d worked for the Freihoeven Institute’s ParaPsych Department—two during his internship, five after—Sy was pretty sure this was the first and only time he’d ever dealt with Carraclough Devize without the presence of Freihoeven head-man Doctor Guilden Abbott, who seemed to consider himself her surrogate father cum self-elected handler. Never forget, Sylvester: Carra is special, Abbott was fond of saying. Our single best resource, the standard by which all other psychic—assets—must be judged. When Doctor and Doctor Jay were doing their initial survey of the greater Toronto area, they concluded they’d never met anyone like her, and never expected to; that’s good enough for me.

Which wasn’t completely true—certainly, Sy’d spent enough time in Records to know that Abbott continued to test Devize’s crazily high ratings bi-annually, regular as seasonalized clockwork. The latest series of arrays usually coincided with whenever she’d checked herself out of the Clarke, which she used like it was either a five-star spa or her summer cottage/winter retreat/spring and fall whatever; special, for sure. In all senses of the word.

Between commitments, Devize spent the bulk of her time at the Freihoeven itself, often even sleeping there (Abbott had assigned her an office, for that very purpose), with very occasional return trips to the basement apartment of her mother’s decaying Annex home. And though records showed she was at least ten years older than Sy, pushing forty harder than a Midvale School for the Gifted student at the door marked “pull,” she still drifted through life displaying all the fine social skills of the child prodigy she’d once been—the thirteen-year-old whose destitute, grief-drunk mother Gala had rented her out to any séance circuit freak seeking solace from beyond the grave. Who, on promise of $10,000 and a “consulting” job, had accompanied the aforementioned Doctor Jay and Jay—Freihoeven’s founders, Abbott’s mentors, both late and lamented—on their extremely unsuccessful final mission.

The goal: catalogue and/or exorcize Peazant’s Folly, a haunted house located on a natural gas fault up near Overdeere, Ontario. The cost: one archaeologist, one forensic psychologist, one well-established mental medium, and two noted parapsychological researchers, all removed in body-bags, straitjackets, or simple police restraints. Devize, the youngest party-member, had been listed as Glenda Fisk’s “apprentice” on the original proposal; she came back in a coma, then woke with a convulsive blast of telekinetic energy that broke all the windows on her floor of the Toronto Sick Kids’ Hospital, signifying her emergence as something entirely new: a mental medium turned physical, ghost-touched from one category straight into another, with little to show for the experience but a broken hip, a lingering limp, and a complete inability to screen herself anymore.

Sy remembered a piece of video footage he’d stumbled on—Abbott’s first interview with Devize after assuming control of the Institute, when she was only two months out of the hospital. Pretty much the same figure as today, barring a few more crow’s feet; downcast face hair-shadowed, eyes glasses-hidden. Blank as any given winter street, snow new-fallen over grime, just waiting for fresh defilement.

You look well, Carra. Better.

Mmm-hmm. Ready for work; that’s what Gala says, anyhow.

Oh well, there’s no immediate need—

No, it’s all right. Take a look: I’m fine, no harm, no foul. No scars . . . but then there wouldn’t be, would there?

Sorry?

Oh, Doctor. And here she almost smiled—almost. Asking, gently: Are you really going to tell me you haven’t noticed?

Sy could still see Abbott’s brows, already too close for comfort, attempting to knit themselves inextricably together. I, uh . . . I don’t understand.

How I have no skin, anymore.

(That’s all.)

And that would be the attraction, right there, ever since: a wound so deep, so all-encompassing and impossible to heal, it practically counted as a super-power. Carraclough Devize, human ghost-o-meter—steer her towards anything suspected of weirdness, sit back, and take notes. By Freihoeven standards, there was no better confirmation/debunking method than letting her wander through a site and come back either edge-of-puking, a-crawl with automatic writing stigmata, or simply shaking her head in that numb, vaguely disappointed way.

The Folly, protected by Historic Site status, had finally been converted into a haphazard tourist attraction; it had endured, unoccupied except for half-hour stretches three times a day, until 2002, when the lights went out during a lecture and the tour-guide’s assistant lit a candle. Meanwhile, the Freihoeven prospered, even without the Jays. Guilden Abbott kept his job, and so long as he did—apparently—so did Carra Devize.

Incautious, that last observation. Sy felt her prying absently at the edges of his brain again, perhaps without even meaning to—her half-hearted attention in the back of his mind like grit, sanding a horrid pearl.

“Where is Abbott, anyways?” she asked, turning the camera over in her hands, rather than probe any deeper. Which was . . . nice of her, he guessed. Jesus, I’m bad at this.

Not like he’d never dealt with psychics before, for Christ’s sake. Just not ones this strong or competent. Or unpredictable.

“He had to go to the States, on very short notice. Boston.”

“Lecture?”

“Estate sale, actually. Plus a silent auction, by the candle.”

“Huh.”

(Fitting.)

They were almost to the gate now, Sy waving at the orderly who’d let him in, who nodded, curtly. Turning Devize’s way, he reminded her, voice softening: “You need to be back by five, Carra.”

“I know, Paul.”

“Five, on the dot. Or we gotta put you back in the no-sharps room.”

She made a clumsy okay sign with both hands, thumbs barely meeting forefingers; tendons might be still a bit foreshortened from the patch-job, Sy supposed. “I know, Paul. Seriously.”

“Well, just sayin’. You been here long enough.”

As the contact gate screeched open, Sy stepped through with her on his heels, uncomfortably close. He felt, rather than saw, her give that same slight head-shake, a bit sadly.

“Not quite yet,” he thought he heard her murmur, under the alarm’s screech.

Spirit Cabinet, circa 1889, the label read, in Abbott’s neat handwriting. From the estate of Katherine-Mary des Esseintes/Lardner-Honeycutt crime scene (transfer handled by Wilcox Labrett Oyosolo, 2007, through Auction-House Miroux).

And: “Oh,” Devize said, behind him, to no one in particular, “that box.”

This was Freihoeven’s second storage unit, three whole hallways deeper inside the facility than their first. Though Sy had overseen its rental, it’d been long-distance; before today, he’d never had occasion to step inside its echoing metal shell. Beneath their feet, the concrete floor sent up enough dust to hang visible, stinging in the nose.

The cabinet was a one-slot variation on the Davenport brothers’ original 1854 model, only slightly less compact than your average

Ikea dresser. Dark, burnished wood with plain brass fittings. A small window with a scrim, confessional-style. Inside, Sy assumed, there’d be a coffin-like space for the medium to sit, perhaps even a system of restraining straps—first tied down in public, doors wide, then locked away, with one of the séance-goers being given the key.

He walked around it, feeling for joins, and found none. Which didn’t prove anything, necessarily . . . but des Esseintes had had a good reputation, as he recalled, given the hotbed of fakery most 1800s Spiritualism grew out of. Like Devize, she’d worked under the care of her mother, whose chaperone-like presence served to fend off fetishists—until her demise, upon which des Esseintes’ main patron became her husband, forcing her to retire. A year later des Esseintes was also dead, predictably, in childbirth.

As he rounded the cabinet’s left wing, a dry kissing noise and flashbulb-pop made Sy start. Once again, he found Devize so close he almost collided with her. “Wouldn’t’ve thought they’d let him have this, after what happened,” she remarked, shaking her first shot out and squinting at the result. “But then again, I guess that’s what the acquisitions budget’s for.”

“People were pretty generous this year, at the fundraiser.”

“I can see that. Sorry I had to miss it.”

“We, uh, missed you, obviously. But—”

“Oh, I’m sure the demo went off like a charm; Abbott’s building a nice little roster of alternates. I vetted most of them. Who was it—Jodice Glouwer, Suzy Shang? Janis Mol?”

“Miss Glouwer’s hard to reach, these days.”

“Janis, then—that’s good. She needs the work.”

Two more shots in quick succession, seemingly intentionally angled to give Sy a headache. He moved off, looked away, studying the wall; she brushed past, still clicking and shaking. A fistful of slimy-faced, sharp-smelling squares already fanned out between her fingers, like cards from some weird deck. Indicating them, he asked: “Anything interesting?”

We Will All Go Down Together

We Will All Go Down Together